From Hamilton’s time to the present, Paterson has been a city of workers, many coming from other countries to seek a better life for their families. For more than a century, Paterson also was a nationally known battleground in the struggle between employers and workers. A Paterson labor leader came up with the idea of celebrating workers on what would become the national holiday, Labor Day.

From Hamilton’s time to the present, Paterson has been a city of workers, many coming from other countries to seek a better life for their families. For more than a century, Paterson also was a nationally known battleground in the struggle between employers and workers. A Paterson labor leader came up with the idea of celebrating workers on what would become the national holiday, Labor Day.

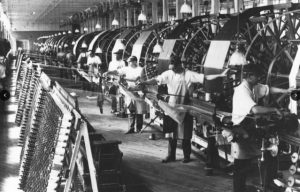

Paterson played a major role in the growth of the labor movement. In 1828, cotton workers quit their looms to protest a change in the lunch hour from noon to 1:00 pm. Carpenters, masons, and mechanics in Paterson also walked out of their jobs in a sympathy strike. The workers did not initially succeed, but not long after the strike, the owners restored the noon lunch hour.

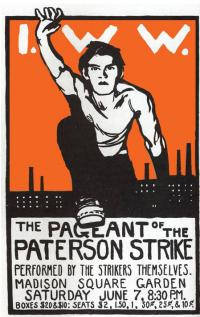

At the peak of the city’s international dominance of the silk industry, the Paterson Silk Strike of 1913 erupted involving more than 25,000 workers in some 350 plants. Led by the radical Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.), the workers sought to maintain a system that each worker would handle two looms at a time that the owners planned to increase the number each worker would have to handle.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, “Big Bill” Haywood, Carlo Tresca, and John Reed came to lead the picket lines. When one striker was killed, more than 15,000 workers joined the funeral procession. Workers, who were not permitted by local police to rally in Paterson, held mass meetings on a large field in front of the Botto Family House in the neighboring town of Haledon that had elected a Socialist mayor in 1912.

John Reed, the young Harvard graduate portrayed by Warren Beatty in the movie “Reds,” staged the famous “Paterson Pageant” in Manhattan’s Madison Square Garden to call attention to the plight of the workers and try to raise money to help them. The artist John Sloan designed the stage sets for the event, and other artists, poets, and Greenwich Village intellectuals worked to support the cause. After five months without work or pay, the workers went back to the silk factories in defeat.

In the last three decades, scholars completed new research on both the Paterson silk strike and the Paterson Strike Pageant, concluding that the 1913 strike challenged certain widely held assumptions about social  movements and labor history. Although many had thought that skilled workers were elitist, in Paterson skilled weavers began the strike and promptly reached out to unskilled workers. Union organizers actively encouraged the emergence of rank-and-file leaders, particularly women.

movements and labor history. Although many had thought that skilled workers were elitist, in Paterson skilled weavers began the strike and promptly reached out to unskilled workers. Union organizers actively encouraged the emergence of rank-and-file leaders, particularly women.

Silk and other textile manufacturing have declined, but Paterson remains a place for laborers.

Additional Resources