Modern Silk Road

By the 1880s, Paterson, New Jersey, was the center of the global silk trade. Known as “The Silk City,” Paterson became the final stop for a trade route that transported goods and ideas across three continents. The Modern Silk Road Virtual Exhibit, funded by the National Endowments for the Arts and the New Jersey Council for the Humanities, explores the 2,200-year journey that brought the silk trade to Paterson and how this fabric shaped Paterson’s economy, culture, and people.

The Silk Road began in the 2nd century BCE when the Han Dynasty of China expanded west of the Great Wall. The Chinese brought silk into an existing network that traded livestock, goods, culture, and ideas amongst each other and across Eurasia as far west as Rome and Egypt. China’s entrance into the global trade network with its abundance of fine silk, shifted the focus of culture and commerce of the ancient world.

Silk had long been prized in China as a luxury good, a status symbol, and even as a commodity. While grain rotted over time and coins were not universally accepted the further one got from urban centers, bolts of silks served as the payment of soldiers and tributes for raiding nomadic tribes.

``Silk became both a component and a symbol of this cultural diffusion. It was seen as a valuable index of civilization with regard to religious ritual, kingship, artistic production, and commercial activity. Silk stood for the higher things in life. It was a valuable, traded commodity, as well as a historical medium of exchange.``

China enjoyed a near monopoly on silk sericulture and weaving for 3000 years. Eventually, silk farming moved east to Japan and the Korean Peninsula and west to India. The cost of silk was equal to the price of gold in the Roman Empire. European empires shipped precious metals, silver, and gold to correct the trade imbalance with Asia. In the sixth century, the Byzantine Empire successfully cultivated silkworms and the mulberry trees required to make silk.

The Silk Roads operated until the 15th century when the Ottoman Empire’s conquest of Constantinople closed the European land connection to Asia and the Middle East. However, city-states surrounding the Mediterranean established silk sericulture and silk weaving of their own.

With the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the use of sea routes would become the only way for large quantities of Asian silk to reach Europe. However, centuries before the Byzantium Empire’s reign ended, Italian city-states secured multiple sources of silk. Among the Italian cities, the Genoese merchants dominated trade in the Black Sea, and Venetians controlled a large portion of trade in the Mediterranean.

Sicily became the most notable early producer of silk in Italy as Byzantine silk weavers sought refuge on the island. Silk production became so prominent in the 12th century that Ruggero II, King of Sicily, constructed silk factories next to his palace in Palermo. In Genoa, Tuscany, Venice, and Naples, tens of thousands of silk spinners, weavers, and dyers were employed.

Italian merchants supplied silk to northern and western Europe. In the 13th and 14th centuries, Venetians and Genoese merchants sold large quantities of silk at fairs across Europe. One of the most famous was the Champagne Fair in France, which sourced silk fabric to central France, including Lyon.

By the 16th century, the center of silk production moved to Lyons. The southern French city produced nearly two-thirds of all silk imports from Italy. By the end of the century, France went from producing no raw silk to creating two to three million pounds each year.

Among the growing class of French silk workers were Huguenots, French Protestant Reformers that populated southern and northeastern France. In the 1680s, King Louis XIV escalated his harassment and persecution of Huguenots and other Protestants by ordering the destruction of their churches and schools. This event was known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and it forced the mass migration of Huguenots. Scholars considered Huguenots to be the first refugees.

Nearly 150,000 Huguenots fled France over the course of a decade. They brought their trades of olive oil making, winemaking, and silk production to new settlements in North America, South America, Prussia, Holland, and across the English Channel.

In England, the refugees created ethnic neighborhoods, the largest being in the London suburb of Spitalfields, where they established England’s first thriving silk industry.

As the silk weaving and threading trades spread across the country, landowners in smaller towns and villages paid tenants to manufacture fine silk goods. By 1698, manufacturing silk buttons became a thriving business in the town of Macclesfield. By the mid-1700s, silk button making became more profitable than farming.

Copyright of Macclesfield Museums

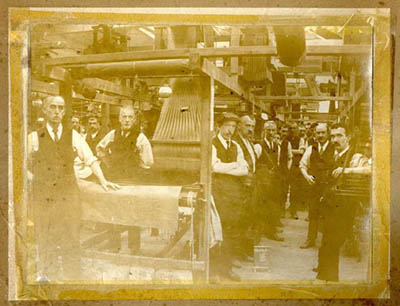

- Inside the weaving shed at the Macclesfield Silk Manufacturing Society mill at London Road in 1900

- Drawing Silk

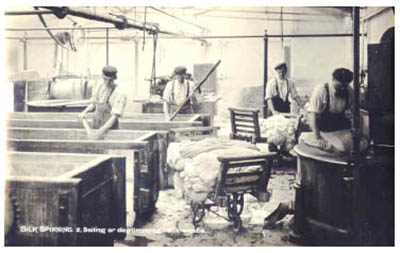

- Silk Boiling, Hurdsfield Mill

- Receiving Raw Silk, Hurdsfield Mill

- Spinning, Hurdsfield Mill

Macclesfield expanded into the silk-throwing business, providing silk thread for the weavers of Spitalfields. Twelve to fifteen thousand people were employed as silk throwers or weavers, turning the wasted silk into ferrets, stockings, knee garters, and sewing silk.

The introduction of waterpower machinery to Macclesfield by Charlie Roe led to automated silk spinning and weaving. This innovation reduced the number of workers needed and began the industrialization of textile manufacturing. By the mid-1800s, Macclesfield became the dominant silk town in England.

One mill superintendent from Macclesfield would bring the techniques and technology from England’s silk capital to Paterson, New Jersey. As a result, Paterson would become the silk capital of the world.

As the nation’s first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton worked to transform the country from an agrarian economy to a manufacturing economy. As a Lieutenant Colonel in the Continental Army, Hamilton recognized the colonials would never achieve true independence without a domestic manufacturing industry that could produce finished goods but, most importantly, military supplies.

Hamilton laid out his economic vision to Congress in the Report on the Subject of Manufacture. Within the report, Hamilton advocated for public investment in manufacturing. The plan was not fully adopted, so Hamilton and Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, Tench Coxe created a public-private partnership to serve as an industrial incubator similar to Silicon Valley.

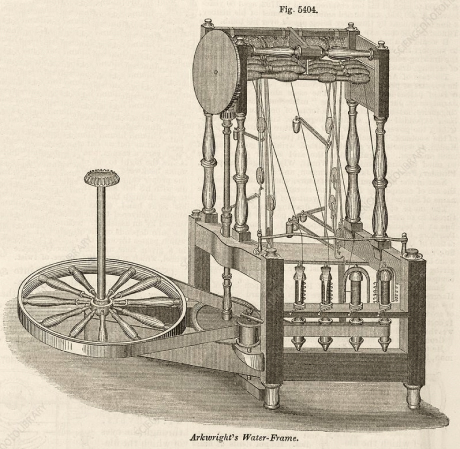

The Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.) provided the capital investment necessary to build a mill town from scratch. Coxe dispatched an agent to England to steal trade secrets and patents for textile machinery. Coxe recruited George Parkinson to bring the design secrets to recreate the water wheel to America. Parkinson’s design included a number of improvements that allowed the manufacturing of hemp, flax, worsted, and silk goods. Next on Coxe’s agenda is where to build Hamilton’s City of the Future.

“As a Lieutenant Colonel in the Continental Army, Hamilton recognized the colonials would never achieve true independents without a domestic manufacturing industry that could produce finished goods but most importantly military supplies.”

Hamilton and Coxe agreed the town should be located in New Jersey (close to the New York market and financiers) and near a river. Hamilton chose a site near the Passaic River Falls. He was familiar with the site as he, George Washington, and the Marquis de Lafayette picnic next to the falls a few days after the Battle of Monmouth. Almost fifteen years later, Hamilton did not forget the awe-aspiring power of the 77-foot-high and 260-foot-wide falls moving water at a rate of more than 2 billion gallons daily.

Hamilton hired engineer Pierre L’Enfant, the city planner of Washington D.C., to design a raceway or canal system that could harness the rapids from the Passaic River near the top of the falls. The raceway would power the mills and factories in the newly chartered town named after the state governor William Paterson. After several unsuccessful attempts to cut costs in L’Enfant’s original raceway design, Peter Colt—then the administrator of the S.U.M. and uncle of Samuel Colt—successfully facilitated the raceway’s construction. The S.U.M. operated the raceway from 1796 to 1945. Today the system is a dedicated National Historic Mechanical and Civil Engineering Landmark.

Paterson was founded on the promise that a strong domestic manufacturing industry would lead to economic independence from Europe. However, Hamilton’s city of the future needed the skilled labor, machinery, and technical expertise from the old world to carry out his vision. Textile manufacturing, especially silk, in Paterson relied on immigrant labor and capital.

In 1839, John Ryle came to America to expand his family’s silk business, which was already the largest in England. Ryle began manufacturing silk in the Old Gun Colt Mill near the Paterson Great Falls. The Macclesfield native would become the largest silk manufacturer in the United States, earning him the title of “Father of the American Silk Industry.”

Silk manufacturing in Macclesfield began declining in the 1850s and 60s. At the same time, the American Civil War, and its tariffs on imports, such as silk, increased domestic demand. The resulting need for skilled labor in Paterson’s silk mills led many of the Macclesfield workers to relocate to Paterson. By 1900, as many as 15,000 Macclesfield natives worked in Paterson.

The dream of a better life pulled Macclesfield weavers to America. Master weavers from Macclesfield not only worked in the mills but also set up businesses in their homes as the entire family, including children, weaved silk goods on foot looms. By the 1880s, when the Italian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants began working in the silk mills, the first wave of silk workers had climbed the social and economic ladder becoming the bosses and supervisors in the mills.

Paterson’s population ballooned from 19,586 in 1860 to 51,031 in 1880, and by 1900 reached 105,171. As each wave of new immigrants arrived, the make-up of Paterson and the silk industry changed. Italians began a great migration in 1880, two decades after the unification of Italy that lasted until the rise of fascism. Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe created communities in Paterson based on their countries of origins, with communities rising around synagogues near the Passaic River. As these groups joined the Paterson community, they brought their culture and politics from Europe. Socialism, anarchism, and other political ideologies and religions would mix into the American working class’s pursuit of fair wages, better conditions, and trade unionization.

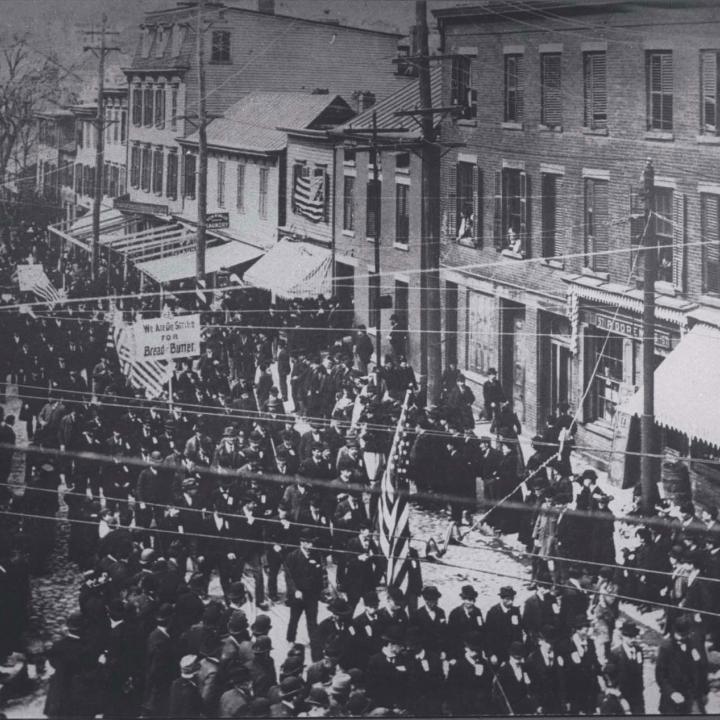

The history of labor in Paterson is sprinkled with strikes. In 1877, silk ribbon weavers held a general strike to fight a 20% wage reduction. Ten years later, silk dyers and ribbon weavers went on strike in two separate labor actions to increase wages. In 1912, the labor divide in silk mills formed across ethnic lines. The earlier waves of silk workers from England, Switzerland, and Germany owned the mills, supervised the shop floors, and worked the skilled positions. In contrast, the new wave of Eastern European and Italian laborers worked unskilled and semi-skilled jobs.

As union participation increased in the mills, Paterson became a site of more frequent labor actions. In 1913, the silk workers called for a general strike. With the backing of the greater Paterson community and the radical Industrial Workers of the World union, they struck for increased wages, improved conditions, and an eight-hour workday. For the first time, the strikers represented the diversity of Paterson’s workforce. Laborers and semi-skilled workers representing a variety of religions, ethnicities, genders, and ages found solidarity which allowed them to hold out for five months.

Silk manufacturing remained in Paterson after the strike but saw marked declines after World War I. The world wars shifted the city’s industrial energy as companies such as Wright Aeronautical brought wartime manufacturing to the Great Falls. Silk eventually left Paterson as mills closed and textile manufacturing moved to the South.

More than 200 years after the founding of Paterson, Hamilton’s city of the future, built on the strength of immigrant labor, remains one of the most diverse cities in the country. Each wave of new immigrants brings their unique culture, identity, and ideas to the city. Throughout the history of Paterson, communities of immigrants settled in different neighborhoods. Today ethnic groups from the Middle East and South Asia, whose ancestors lived along the ancient Silk Roads, have built thriving communities in Paterson.

Once populated with Italian Americans, South Paterson is now home to many Palestinian, Turkish, and Syrian families. Today, people of Middle Eastern descent make up 11% of South Paterson’s population and are concentrated within a few city streets. A highlight of this neighborhood is a vibrant section of Main Street called “Little Ramallah.” Renowned for its markets, shops, lounges, restaurants, and bakeries, “Little Ramallah” is a destination for foodies that has been featured in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and countless other media outlets.

The first Middle Eastern immigrants from Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey arrived in the late 19th century, along with those from Italy and Eastern Europe. In the 1880s and 1890s, Syrians—one of the key ethnic groups that brought silk to Sicily in the 12th century—arrived in Paterson as many groups fled the Ottoman Empire due to religious persecution. In Paterson, Syrian immigrants became traders, street merchants and worked in textile mills. While Syrian silk is prized, the immigrants to Paterson had limited influence on the city’s silk manufacturing.

Bangladeshis, another ethnic group with a rich history of silk and textile weaving, have found a home in today’s Paterson and Bengali is one of the official languages the city uses to communicate with its residents. “Little Bangladesh” is a mere ten-minute walk from the Paterson Great Falls National Historical Park. The very first immigrants from Bangladesh date back to the early 1900s when many worked as stokers heating the vats of dye.